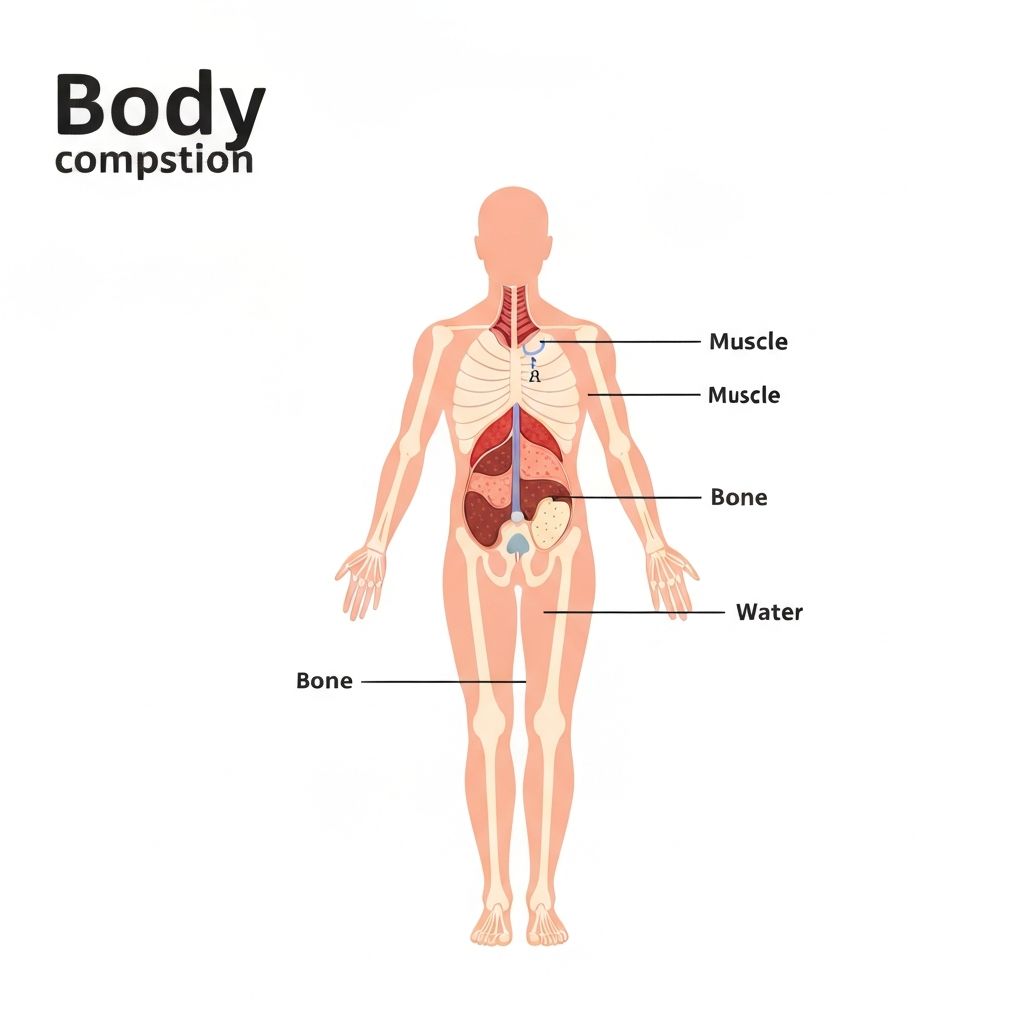

Body Composition Fundamentals

The human body consists of several key components: muscle tissue, adipose tissue (fat), bone, and water. Understanding these components provides a foundation for comprehending how nutrition and physical activity influence body structure. Each component serves distinct physiological roles essential to overall function and health.

Muscle tissue is metabolically active, consuming energy even at rest. Adipose tissue serves as energy storage and produces hormones that regulate metabolism. Bone provides structural support and mineral storage. Water comprises the majority of body mass and participates in all metabolic processes.

Read the full overview →Macronutrient Roles Summary

The three macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—provide energy and perform essential metabolic functions.

Carbohydrates

Primary energy source for brain and muscle. Stored in liver and muscles as glycogen for readily available fuel. Comprise sugars, starches, and fibre with different absorption rates and metabolic effects.

Proteins

Essential for building and maintaining muscle, enzymes, hormones, and immune function. Broken down into amino acids, which are reassembled into body proteins. Each amino acid serves specific metabolic purposes.

Fats

Support hormone production, nutrient absorption, and cell membrane integrity. Provide concentrated energy (9 calories per gram versus 4 for carbs/proteins). Include saturated, unsaturated, and trans-fats with varying effects on metabolism.

Energy Substrate Utilisation

The body utilises available energy sources—carbohydrates, fats, and proteins—as fuel depending on activity intensity, nutritional state, and metabolic conditions. During low-intensity activity, the body preferentially oxidises fat. High-intensity activity relies more on carbohydrate metabolism. Protein is normally preserved for tissue maintenance rather than used primarily for energy. The relative contribution of each substrate shifts throughout the day based on meal timing, exercise, and rest periods.

Satiety Signal Mechanisms

Hunger and fullness are regulated by complex hormonal and neurological signals:

- Leptin — produced by adipose tissue; signals fullness to the brain when energy stores are adequate

- Ghrelin — secreted by stomach; stimulates appetite and food-seeking behaviour

- Peptide YY (PYY) — released by intestines after eating; promotes satiety

- Cholecystokinin (CCK) — triggers fullness signals; released when fat and protein are consumed

- GLP-1 — regulates blood glucose and appetite; released after nutrient intake

- Mechanical Stretch — stomach and intestinal expansion signals fullness independently of nutrient composition

These signals interact constantly, and their sensitivity can be influenced by sleep quality, stress, and habitual eating patterns. Individual variation in satiety signalling is substantial.

Nutrient Timing Effects

The timing of nutrient intake influences metabolic responses. Consuming protein and carbohydrates around exercise windows affects muscle protein synthesis and glycogen replenishment. Larger meals typically produce stronger satiety signals than smaller, frequent meals. Morning nutrition affects hormonal cascades throughout the day. Evening carbohydrate intake influences sleep quality and next-day appetite regulation.

However, individual responses to nutrient timing vary significantly. Total daily intake of macronutrients remains the primary determinant of overall metabolic effects, with timing providing secondary optimisations.

Explore this concept →Physical Activity Types

Different forms of physical activity produce distinct metabolic and physiological responses:

Aerobic Activity

Sustained moderate-intensity movement using oxygen for fuel (running, cycling, swimming). Improves cardiovascular function and burns energy primarily through fat and carbohydrate oxidation.

Strength Training

High-intensity muscle-loading activity using primarily anaerobic metabolism. Drives muscle protein synthesis and increases resting metabolic rate through muscle tissue expansion.

Flexibility & Mobility

Gentle range-of-motion work and stretching. Supports joint health, recovery from other activities, and long-term movement capacity without significant metabolic stress.

Featured Articles

Explore detailed explanations of core nutrition and body composition concepts:

Nutrition Myth Clarifications

Common misconceptions about nutrition and body composition, explained:

- Myth: Carbohydrates are inherently problematic. Fact: Carbohydrates are a primary fuel source; individual responses and overall intake matter more than carbohydrate presence.

- Myth: Fat intake directly causes fat gain. Fact: Total energy intake determines weight change; fat supports essential functions and is calorie-dense (9 calories per gram).

- Myth: Eating late at night causes weight gain. Fact: Total daily intake and activity level are primary determinants; meal timing has secondary effects on metabolic variables.

- Myth: Specific foods "speed up" metabolism significantly. Fact: Macronutrient composition and total intake influence metabolic rate; individual effects are modest.

- Myth: Skipping meals "boosts" fat utilisation. Fact: Total energy balance matters; frequent meal patterns don't inherently affect metabolism differently.

Frequently Asked Questions

Continue Your Learning

This overview provides foundational explanations of body composition and nutrition concepts. Explore our featured articles for deeper understanding of specific topics, or contact us with questions.

View All Articles